Home » History of Vietnam » Tet Offensive » The Tet Offensive

The Tet Offensive

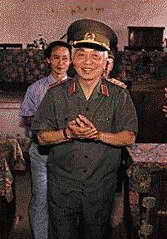

Four-star General Vo Nguyen Giap led Vietnam’s armies from their inception, in the 1940s, up to the moment of their triumphant entrance into Saigon in 1975.

Four-star General Vo Nguyen Giap led Vietnam’s armies from their inception, in the 1940s, up to the moment of their triumphant entrance into Saigon in 1975.

Possessing one of the finest military minds of this century, his strategy for vanquishing superior opponents was not to simply outmaneuver them in the field but to undermine their resolve by inflicting demoralizing political defeats with his bold tactics.

This was evidenced as early as 1944, when Giap sent his minuscule force against French outpost in Indochina. The moment he chose to attack was Christmas Eve. More devastatingly, in 1954 at a place called Dien Bien Phu, Giap lured the overconfident French into a turning point battle and won a stunning victory with brilliant deployments. Always he showed a great talent for approaching his enemy’s strengths as if they were exploitable weaknesses.

Nearly a quarter of a century later, in 1968, the General launched a major surprise offensive against American and South Vietnamese forces on the eve of the lunar New Year celebrations. Province capitals throughout the country were seized, garrisons simultaneously attacked and, perhaps most shockingly, in Saigon the U.S. Embassy was invaded. The cost in North Vietnamese casualties was tremendous but the gambit produced a pivotal media disaster for the White House and the presidency of Lyndon Johnson. Giap’s strategy toppled the American commander in chief. It turned the tide of the war and sealed the General’s fame as the dominant military genius of the 20th Century’s second half.

John Colvin author of “Giap Volcano Under Snow”

This article appeared in the Vietnam Experience

Boston Publishing Company

Giap was prepared to take a gamble. His divisions had been battered whenever they met the American forces in conventional combat and the VC — if not exactly on the retreat — were at least being pushed backwards. Hanoi was perfectly aware of the growing US peace movement and of the deep divisions the war was causing in American society. What Giap needed was a body-blow that would break Washington’s will to carry on and at the same time would undermine the growing legitimacy of the Saigon Government once and for all. In one sense, time was not on Giap’s side. While Hanoi was sure that the Americans would tire of the war as the French had before them, the longer it took, the stronger the Saigon Government might become. Another year or so of American involvement could seriously damage the NLF and leave the ARVN capable of dealing with its enemies on its own. Giap opted for a quick and decisive victory that would be well in time for the 1968 US Presidential campaign.

Giap prepared a bold thrust on two fronts. With memories of the victory at Dien Bien Phu still in his mind, he planned an attack on the US Marines’ firebase at Khe Sanh. At the same time the NVA and the NLF planned coordinated attacks on virtually all South Vietnam’s major cities and provincial capitals. If the Americans opted to defend Khe Sanh, they would find themselves stretched to the limit when battles erupted elsewhere throughout the South. Forced to defend themselves everywhere at once, the US/ARVN forces would suffer a multitude of small to major defeats which would add up to an overall disaster. Khe Sanh would distract the attention of the US commanders while the NVA/VC was preparing for D-day in South Vietnam’s cities but, when this full offensive was at its height, it was unlikely that the over-stretched American forces would be able to keep the base from being overrun and Giap would have repeated his triumph of fourteen years before.It’s highly doubtful that the NVA/VC expected to hold all or even some of the cities and towns they attacked, but the NLF apparently did expect large sections of the urban populace to rise up in revolt. With a few exceptions, this didn’t happen. South Vietnam’s city dwellers were generally indifferent to both the NLF and the Saigon Government but the VC clearly expected more support than it actually got. The object of attacking the cities was not so much to win in a single blow as it was to inflict a series of humiliating defeats on the Americans and to destroy the authority of the Saigon Government. When the US/ARVN forces finally drove the NVA/VC back into the jungle, there would be left behind a wasteland of rubble, refugees, and simmering discontent. Stung by their defeats, the Americans would lose heart for the war and what was left of the Saigon Government would be forced to reach an agreement with the NLF and Hanoi which — after a time — would simply take over in the South. This offensive would begin in January 1968 at the time of the Vietnamese Tet (New Year) holidays.

Click on any image for a full scale JPG

The body of a VC lies in the streets of Saigon hardly noticed by the daily business on the first day of the Tet Offensive. The corpses of three NVA regulars lie in the streets near Saigon’s Old French Cemetery. An ARVN Ranger sprints for cover through the corps-and rubble-filled streets of Cholon.

The village of Khe Sanh lay in the northwest corner of South Vietnam just below the DMZ and close to the Laotian border. Khe Sanh had been garrisoned by the French during the first Indochina war and became an important US Special Forces base early on during the second. Its importance lay in its proximity to the Ho Chi Minh Trail. From Khe Sanh, US artillery could shell the trail and observers could keep an eye on NVA traffic moving southwards. If necessary they could call in air-strikes or alert CIA/Meo raiding parties across the border in Laos. Special Forces working with local Montagnard tribesmen also harried NVA traffic in the area and were a definite nuisance to Hanoi. In 1967, the Marines took over Khe Sanh and converted it into a large fire base. The Special Forces moved their base to the Montagnard village of Lang Vei.

Towards the end of 1967, it was obvious that Giap was planning something. Broadcasts from Hanoi were speaking of great victories and of taking the war into the cities of South Vietnam. Two NVA divisions — the 325th and the 304th — were spotted moving into the Khe Sanh area and a third was positioning itself along Route 9 where it would be able to intercept reinforcements coming in from Quang Tri[?]. The two NVA divisions near Khe Sanh had fought at Dien Bien Phu and the warning was clear. Westmoreland picked up the gauntlet and began to reinforce the base despite predictions of upcoming bad weather which could hinder air support and interfere with vital supply planes. Appearances to the contrary, Westmoreland had no intention of duplicating the French mistakes at Dien Bien Phu. American airpower was capable of delivering devastating attacks on concentrations of enemy troops and — apart from anti-aircraft guns — was unopposed. Helicopters and parachute drops by low-flying cargo planes reduced the dependence on re-supply by road.

By late January, some 6,000 Marines had been flown in to reinforce the Khe Sanh garrison and thousands of reinforcements had been moved north of Hue. The NVA build-up also continued; at least 20,000 North Vietnamese were ultimately moved in around Khe Sanh but some estimates put the number at twice that. Initially, Giap would position his artillery in the DMZ, and then send his assault troops against the fortified hills surrounding Khe Sanh, which the Marines had captured in the dogged fighting in 1967. Having captured the hill positions, Giap reasoned, the NVA artillery could be moved onto the heights above the beleaguered base. Then — as happened at Dien Bien Phu — waves of determined infantry would steadily grind away until the defenders were pushed into a corner and finally over-run. The White House and the US media became convinced that the decisive battle of the war had begun. TV news reports were so obsessed with Giap’s threatened replay of Dien Bien Phu that day-to-day life at Khe Sanh became lead-story material even when it showed nothing other than anxious Marines waiting for something to happen.

The first attack began shortly before dawn on January 21st, when the NVA attempted to cross the river running past the base. It was beaten back but followed by an artillery barrage which damaged the runway, blew up the main ammunition stores, and damaged a few aircraft. Secondary attacks were launched against the Special Forces’ defenses at Lang Vel and against the Marines dug-in on the hills surrounding Khe Sanh, but these attacks were aimed more at testing the defenses than anything else. The next day, helicopters and light cargo aircraft flew in virtually every few minutes replacing lost ammunition, but the weather began turning worse.

Click on any image for a full scale JPG

Marine snipers at Khe Sanh. Marine snipers engaged in long-running duels with NVA marksmen. US fifty caliber machine-gun on the perimeter defense of Khe Sanh.

The NVA began a concentrated artillery barrage and moved their troops forward to begin building a network of entrenched positions in which they could prepare for further assaults on Khe Sanh’s outer defenses. Anti-aircraft guns and the worsening weather made incoming supply flights difficult. [running skirmishes designed to break through on Route 9]. Air and supporting US forces moved up to engage the NVA in running skirmishes around Khe Sanh. [?]were intensified and despite the weather, pounded the North Vietnamese hour after hour. Electronic sensors of the types running along the McNamara Line surrounded Khe Sanh. Seismic and highly sensitive listening devices enabled the Americans to monitor everything from normal conversations to radio communications. Overhead, high-flying signal-intelligence (SIGINT) aircraft intercepted communications traffic over the entire front, and to and from command centers in North Vietnam.

While the world was watching the drama unfolding at Khe Sanh, however, NVA and VC regulars were also drifting into Saigon, Hue, and most of South Vietnam’s cities. They came in twos and threes, disguised as refugees, peasants, workers, and ARVN soldiers on holiday leave. In Saigon, roughly the equivalent of five battalions of NVA/VC gradually infiltrated the city without anyone informing or any of the countless security police taking undue notice. Weapons came separately in flower carts, jury-rigged coffins, and trucks apparently filled with vegetables and rice. There was also a VC network in Saigon and the other major cities, which had long stockpiled stores of arms and ammunition drawn from hit-and-run raids or bought openly on the black-market. It was also no secret that VC drifted in and out of the cities to see relatives and on general leave from their units. Viet Cong who were captured during the pre Tet build up were mistaken for regular holiday-makers or deserters. In the general pattern of the New Year merry-makers, the VC’s secret army of infiltrators went completely unnoticed.Tet had traditionally been a time of truce in the long war and both Hanoi and Saigon had made announcements that this year would be no different — although they disagreed about the duration. US Intelligence had gotten wind that something was brewing through captured documents and an overall analysis of recent events, but Westmoreland’s staff tended to disregard these generally vague reports. At the request of General Frederick Weyand, the US commander of the Saigon area, however, several battalions were pulled back from their positions near the Cambodian border. General Weyand put his troops on full alert but — due to a standing US policy of leaving the security of major cities to the ARVN — there were only a few hundred American troops on duty in Saigon itself the night before the attack began. Westmoreland later claimed to have anticipated Tet but the evidence suggests that he was not prepared for anything approaching the intensity of the attack that came and that he was still concentrating his attentions on the developing battle at Khe Sanh where he thought Giap would make his chief effort.

In the early morning hours of January 31st, the first day of the Vietnamese New Year, NLF/NVA troops and commandos attacked virtually every major town and city in South Vietnam as well as most of the important American bases and airfields. There were some earlier attacks around Pleiku, Quang Nam, and Darlac but these were largely misinterpreted as the enemy’s main thrust by those who were expecting some activity during Tet. Almost everywhere the attacks came as a total surprise. Vast areas of Saigon and Hue suddenly found themselves “liberated” and parades of gun-waving NVA/VC marched through the streets proclaiming the revolution while their grimmer-minded comrades rounded up prepared lists of collaborators and government sympathizers for show trials and quick executions.

In Saigon, nineteen VC commandos blew their way through the outer walls of the US Embassy and overran the five MP’s on duty in the early hours of that morning. Two MP’s were killed immediately as the action-team tried to blast their way through the main Embassy doors with anti-tank rockets. They failed and found themselves pinned-down by the Marine guards, who kept the VC in an intense firefight until a relief force of US lO1st Airborne landed by helicopter. By mid-morning, the battle had turned. All nineteen VC were killed, their bodies scattered around the Embassy courtyard. Five Americans and two Vietnamese civilians were among the other dead. The commandos had been dressed in civilian clothing and had rolled-up to the Embassy in an ancient truck. The security of the Embassy was not in serious danger after the first few minutes and the damage was slight but this attack on “American soil” captured the imagination of the media and the battle became symbolic of the Tet Offensive throughout the world. Other NVA/VC squads attacked Saigon’s Presidential Palace, the radio station, the headquarters of the ARVN Chiefs of Staff, and Westmoreland’s own MACV compound as part of a 7O0 man raid on the Tan Son Nhut air-base. During the heavy fighting that followed, things became sufficiently worrying for Westmoreland to order his staff to find weapons and join in the defense of the compound. When the fighting at Tan Son Nhut was over, twenty-three Americans were dead, eighty-five were wounded and up to fifteen aircraft had suffered serious damage. Two NVA/VC battalions attacked the US air-base at Bien Hoa and crippled over twenty aircraft at a cost of nearly 170 casualties. Further fighting at Bien Hoa during the Tet offensive would take the NVA/VC death total in Saigon to nearly 1200. Other VC units made stands in the French cemetery and the Pho Tho race track. The mainly Chinese suburb of Cholon became virtually a NVA/VC operations base and, as it later turned out, had been the main staging area for the attacks in Saigon and its immediate area. President Thieu declared Marshal law on January 31st but it would take over a week of intense fighting to clear-up the various pockets of resistance scattered around Saigon. Sections of the city were reduced to rubble in heavy street-by-street fighting. Tanks, helicopter gunships, and strike aircraft blasted parts of the city as entrenched guerrillas fought and then slipped off to fight somewhere else. The radio station, various industrial buildings, and a large block of low-cost public housing were leveled along with the homes of countless civilians who were forced to flee. The city dissolved into chaos which took weeks to begin to put right.

The fighting within Saigon itself was pretty much over by February 5th but it carried on in Cholon until the last week of the month. Cholon was strafed, bombed, and shelled but the NVA/VC held on and even mounted sporadic counter-offensives against US/ARVN positions within the city and against Tan Son Nhut airport. B-52 strikes against communist positions outside Saigon came within a few miles of the city. When the NVA/VC were finally driven out of Saigon’s suburbs, they retreated into the surrounding government villages and fought there. US and ARVN artillery and strike-aircraft bombed and shelled these supposedly pacified villages before troops moved in to reoccupy them. The NVA/VC repeated this tactic again and again in a clear effort to make the Saigon Government destroy their own fortified villages and, by doing so, further alienate the rural population. A month after the offensive began, US estimates put the number of civilian dead at some 15,000 and the number of new refugees at anything up to two million and still the battles went on.

Elsewhere in South Vietnam, the success of the Tet offensive was erratic. Many of the attacks on the provincial cities and US bases were easily beaten back within the first minutes or hours, but others involved bitter fighting. In the resort city of Dalat, the ARVN put up a spirited defense of the Vietnamese Military Academy against a determined VC battalion. Fighting raged over the Pasteur Institute — which changed hands several times — and the VC dug themselves in [at?] the central market. Fighting in Dalat went on until mid-February and left over 200 VC dead. In cities like Ban Me Thuot, My Tho, Can Tho, Ben Tre, and Kontum, the VC entrenched themselves in the poorer sections and held out against repeated efforts to push them out. The biggest battle, however, occurred at Hue.

The Buddhist crisis had left bitter feelings towards the Saigon Government in the ancient Vietnamese capital and, within a few hours of their attack, the disguised insurgents supported by some ten NVA/VC battalions had overrun all of the city except for the headquarters of the ARVN 3rd Division and the garrison of US advisors. The main NVA/VC goal was the Citadel, an ancient imperial palace covering some two square miles with high walls several feet thick. NVA troops assaulted the Citadel and ran up the VC flag on the early morning of January 31st but were unable to displace ARVN holding out in the northeast section. Having overrun the city and found considerable support among sections of Hue’s populace, the NVA/VC began an immediate revolutionary “liberation” program. Thousands of prisoners were set free and thousands of “enemies of the state” — government officials, sympathizers, and Catholics — were rounded up and many were shot out of hand on orders from the security section of the NLF which had sent in its action squad with a prepared hit-list. Most of the others simply vanished.

After Hue was finally recaptured at the end of February South Vietnamese officials sifting through the rubble found mass graves with over 1200 corpses and-sometime later-other mass burials in the provincial area. The total number of bodies unearthed came to around 2500 but the number of civilians estimated as missing after the Hue battle was nearly 6000. Many of the victims found were Catholics who sought sanctuary in a church but were taken out and later shot Others were apparently being marched off for political “re-education” but were shot when American or ARVN units came too close.

The mass graves within Hue itself were largely of those who had been picked up and executed for various “enemy of the people” offenses. There is some doubt that the NVA/VC had planned all these executions beforehand but unquestionably it was the largest communist purge of the war.

US Marines and ARVN drove into the city and, after nearly two days of heavy fighting, secured the bank of the Perfume river opposite the Citadel. Hue was a sacred city to the Vietnamese and apart from the ancient Citadel held many other precious historical buildings. After much deliberation, it was reluctantly decided to shell and bomb NVA/VC positions. Resistance was heavy and sending the Marines into the city without air and artillery support would have meant an unacceptable cost in lives. To many, the battle for Hue reminded them of the bitter street-by-street fighting that occurred during World War lI. The NVA had blown the main bridge across the Perfume River. US forces crossed in a fleet of assault craft under air and artillery cover which blasted away at the enemy-held Citadel. Its walls were so thick that few were killed but the covering fire made the enemy keep their heads down while the Marines and soldiers hit the bank below.

While the ARVN, with US support, fought its way through the streets of Hue block by block, the Marines prepared to assault the Citadel. On February 2Oth American assault teams went in through clouds of tear gas and the burning debris left over from air and artillery attacks. The NVA/VC were pushed into the southwestern corner of the Citadel and finally overwhelmed on February 23rd. Enemy resistance in Hue was finally reduced to isolated pockets and sniper teams. As the Citadel fell, NVA/VC units began retreating — some of them marching groups of soon to be massacred prisoners before them — into the suburbs while their rear guards fought holding actions with the advancing ARVN. The fight for Hue ended by February 25th at a cost of 119 Americans and 363 ARVN dead compared to about sixteen times that number of NVA/VC dead.

Click on any image for a full scale JPG.

Marines battling with VC/NVA sniper fire behind a wall near the enemy-held Citadel in Hue. Marines jury-rig a machine gun rest to return VC/NVA fire in Hue.

The dramatic difference in fatalities makes the battle look a one sided affair. But it wasn’t! The difference in casuaity figures came largely from the heavy use of artillery and aircraft back-up to devastate NVA/VC positions throughout Hue which reduced large sections of the city to body-laden piles of rubble. Had the commanders decided to preserve the ancient and revered city US/ARVN casualties would have been much higher. American wounded during the battle for Hue came to just under a thousand, compared to slightly over 1,200 ARVN. Nearly 120,000 citizens of Hue were homeless and, of the close to 6,000 civilian dead, many died in the bombing and shell-fire.

Contrary to many reports, large sections of Hue escaped relatively undamaged, but after the battle they were forced to suffer days of looting by soldiers from the original ARVN garrison, who had spent the previous weeks keeping their heads low. Their commander — who had also sat out the city’s Buddhist rebellion against Ky — was later accused of having known about the coming attack for days beforehand. His defense was that he had allowed the NVA/VC battalions into Hue in order to spring a trap! In the villages outside Hue, the battle went on for another week or so as the retreating NVA/VC took over the villages just long enough for them to be destroyed by bombing and concentrated artillery shelling. Civilian deaths and refugees increased.

On February 5th, the fighting died out in Saigon, and the Marines prepared for their river assault on the Citadel in Hue. The electronic sensors around the besieged fire-base at Khe Sanh warned of enemy preparations to assault the entrenched positions on Hill 881, which was outside the main camp. Intensive artillery fire broke up the assembling NVA troops, but a second planned attack on Hill 881 had gone unnoticed until the Marines found themselves fighting off waves of oncoming North Vietnamese regulars. For half an hour the beleaguered Marines battled the NVA in hand-to-hand fighting — even trusting their flak jackets enough to use grenades at close quarters — until the artillery could be brought to bear on the hill and the attackers forced to withdraw.

Click on any image for a full scale JPG.

173 Airborne waiting to move up on Hill 875. Members of the 173rd Airborne dig themselves in in former NVA bunkers after the first stages of the battle for Hill 875.

Two days later, the Green Beret’s camp at Lang Vei was attacked by an NVA assault force led by ten Soviet-built, FT-76 light, amphibious tanks. Despite a shortage of anti-tank ammunition, three of the armored vehicles were put out of action before the NVA swarmed over the wire. Because of the very real likelihood of an ambush, no relief force was sent and the Lang Vei commander, Captain Frank Willoughby, ordered his men into the jungle, and called down air and artillery strikes directly onto the camp. Of the original force of twenty four Special Forces and 900 Montagnard, only Willoughby and seventy-three others managed to struggle into Khe Sanh. The next day NVA troops overran nearly half of an outer Marine position at Khe Sanh before being blasted back by artillery, aircraft, and armor.

Giap’s ambition to win a massive victory against the Americans was thwarted by massive aerial bombardments of NVA positions. B-52’s and strike aircraft dropped their loads, with pin-point accuracy, within a few hundred feet of Khe Sanh’s perimeter. During the course of the battle, tons of bombs and napalm were dropped around Khe Sanh. Bad weather and increasing anti-aircraft fire inhibited the steady flow of incoming supplies, but the vital cargo planes and helicopters kept coming despite losses. The fortified hills around Khe Sanh were supplied by Sea Knight Helicopters, frequently accompanied by fighter escorts. The battle settled down into a siege. The NVA concentrated on shelling the base and trying to stop the supply planes with anti-aircraft fire, while digging in around the camp. Both sides employed teams of snipers to harass each other’s movements.

The NVA launched further attacks on February 17th, 18th, and [1?]9th. Massed artillery and air-strikes broke the first up fairly easily, while the second involved heavy fighting [third?]. In early April, relief forces reached the base. A 1st Cavalry helicopter assault force landed near Khe Sanh as American and ARVN forces hit NVA positions along Route 9. Khe Sanh was relieved on April 6th and, four days later, Lang Vei was re-occupied. Fighting continued around Khe Sanh for a time but Giap had long since given up any hope of overrunning the base. The drive to relieve Khe Sanh had gone smoothly and without heavy resistance. From this, many inferred that the whole siege of Khe Sanh had been a feint to cover preparations for the Tet Offensive in the South. And to an extent, this was true, but the evidence suggests that Giap’s moves on Khe Sanh had a more deadly purpose than simply drawing American attentions away from the South at the critical time. By the middle of February it was obvious that the battle for South Vietnam’s cities was failing and that US airpower would deny the NVA another Dien Bien Phu. Seeing the inevitable, Giap seems to have begun a slow wind-down of the siege before the US counter-attack began.

The After-Effects Of Tet

The Tet Offensive and Khe Sanh may well have reminded Johnson and Westmoreland of the Duke of Wellington’s dictum:

“If there’s anything more melancholy than a battle lost, it’s a battle won”. Giap had been frustrated at Khe Sanh and defeated in South Vietnam’s cities. NVA/VC dead totaled some 45,000 and the number of prisoners nearly 7000. But the shockwave of the battle finished Johnson’s willingness to carry on. Westmoreland was pressuring Washington for 206,000 troops to carry on the campaign in the South and to make a limited invasion of North Vietnam just above the DMZ. As the battle for Hue died out, Johnson asked Clark Clifford (who had recently replaced a disillusioned McNamara as Secretary of Defense) to find ways and means of meeting Westmoreland’s request.

Clifford and an advisor group looked at the war to date, and among others, consulted CIA Director Richard Helms who presented the Agency’s gloomy forecasts in great detail. On March 4th Clifford told Johnson that the war was far from won and that more men would make little difference. Johnson then turned to his chief group of informal advisors (which included among others, Generals Omar Bradley, Matthew Ridgway, and Maxwell Taylor; Cyrus Vance, Dean Acheson, and Henry Cabot Lodge). Johnson soon found that they too, like Clifford, had turned against the war. According to Thomas Powers, Johnson’s “wise old men” had been told that recent CIA studies showed that the pacification programme was failing in forty of South Vietnam’s forty-four provinces and that the NLF’s manpower was actually twice the number that had been estimated previously. Not only had Tet shown that the optimism of the previous year had been an illusion, but it now seemed that the enemy was far stronger than anybody had thought, and that the long efforts to win Vietnamese “hearts and minds” had largely been a disaster.

If Tet wasn’t a full-scale shock to the American public, it was at the very least, an awakening. The enemy that Johnson and the generals had described as moribund had shown itself to be very alive and, as yet, unbeaten. America and its ARVN ally had suffered over 4,300 killed in action, some 16,000 wounded and over 1,000 missing in action. The fact that the enemy suffered far more and had lost a major gamble mattered little, because the war looked like a never ending conflict without any definite, realistic objective. The scenes of desolation in Saigon, Hue, and other cities looked to be war without purpose or end. Perhaps the most quoted US officer of the time was the one who explained the destruction of about one-third of the provincial capital of Ben Tre with unintended black humor: “It became necessary to destroy it,” he said, “in order to save it”. For many, this oft-quoted statement was not just a classic example of Pentagon double-think but also a symbol of the war’s futility. Westmoreland became the parody “General Waste-mor-land” of the anti-war movement.

Being against the war became more-or-less politically respectable for liberal elements. Robert Kennedy spoke of giving up the illusion of victory, and Democratic Senator Eugene McCarthy challenged Johnson for the Presidential nomination on a peace platform. He was supported by thousands of students and young Americans opposed to the war. Vocal elements of the extreme right largely supported the war, but condemned the Administration for not going all out for victory. The JCS backed Westmoreland but convinced him to settle for half of the over 200,000 additional troops he wanted to take the initiative. The JCS then reported to the White House that the extra men were needed to get things back to normal following the battles of the Tet Offensive.

Johnson’s dilemma was complete. He couldn’t meet the generals’ manpower requests without either depleting Europe of American troops — which was unacceptable — or calling up the active reserves — which would have been a political disaster. His most senior advisors had turned against the war and Johnson took another briefing from the CIA analyst whose gloomy reports had soured some of his most hawkish counselors. A few days after this briefing, Johnson went on TV to announce a bombing halt of the North and America’s willingness to meet with the North Vietnamese to seek a peace settlement. Johnson then said that he was not a candidate for reelection under any circumstances and would spend the rest of his term in a search for peace in Indochina.

One of those present at the special CIA briefing which convinced Johnson that a change of course was inevitable was General Creighton Abrams, Westmoreland’s deputy commander. Shortly after Johnson’s turnabout, Abrams replaced Westmoreland as head of US forces in Vietnam. Westmoreland came home to become Army Chief of Staff — a move many saw as a kick upstairs — but, whatever the reasons behind the changeover, Abrams went to Saigon with a mission. He was to institute a program of “Vietnamization”. In other words, to take all necessary measures to enable the ARVN to bear the main burden of the fighting, and gradually return the chief role of American troops to that of advisors. Vietnamization had always been a feature of America’s role in Vietnam, but it had been on a back-burner since 1965 when it seemed that Saigon was incapable of doing the job. Now things were to be returned to what they were supposed to have been from the beginning. Vietnamization is usually credited to Nixon, but it began in the wake of the Tet Offensive and Johnson’s turnabout.

Giap’s gamble had another side effect. When the Tet Offensive began, many US officials believed that the NLF had offered the Americans a golden opportunity by fighting a pitched battle where it could be defeated in open combat. In effect, the NLF was “leading with its chin” and the massive losses it suffered bear this out. The VC was not broken by the Tet Offensive but it was severely crippled by it and, from then on, the North took on the main burden of the war. Further fighting in 1968 and the increasing activity of the Phoenix Program further decimated the NLF’s ranks and the role of the North grew even larger. The northern and southern parts of Vietnam had ancient cultural and social differences, and while the communist cadres at the center of the NLF had managed largely to suppress these natural antagonisms, there still were basic differences in goals and approach. The NLF had gone into the Tet Offensive in the hope of giving a death-blow to the Saigon Government and, if it couldn’t capture power directly, it could at least gain a coalition leading to ultimate authority. The NLF’s dream vanished in the rubble of South Vietnam’s cities, and it would be Hanoi that conquered Saigon.

Taken from the Vietnam Experience Ninteen Sixty-Eight.