Tet Offensive

President John F. Kennedy at his inauguration on January 20, 1961. In his address, the young President summoned the nation to “pay the price, bear any burden…to assure the survival and the success of liberty” throughout the world.

Vietnamese tradition held that the turning of the lunar year should bring auspicious signs and gladness of heart; thus it had become customary for both sides to observe a truce during the holidays celebrations. In 1968, a thirty-six hour cease-fire had been agreed upon, to commence at midnight on January 30.

Centuries before, Vietnam had won a great victory in her running war with the Chinese by attacking their Hanoi garrison at the feight of the Tet observances. In 1968, the Communist led forces in vietnam chose to creat their own auspicious signs by repeating history.

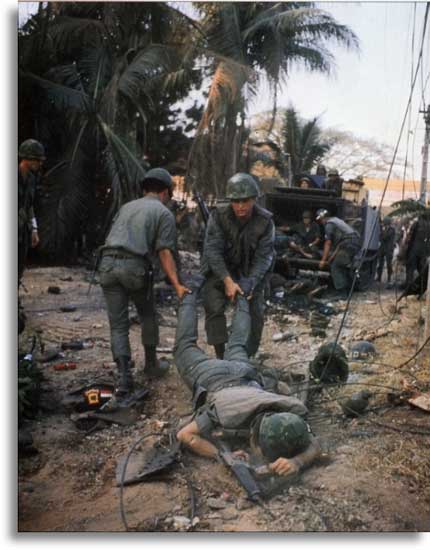

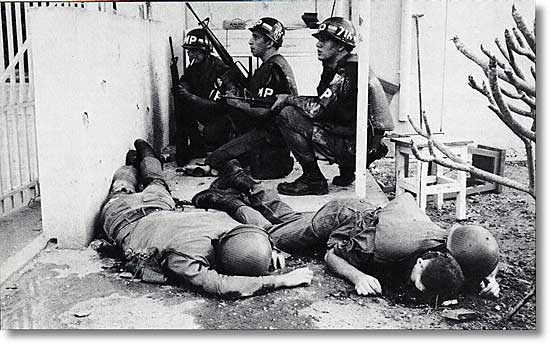

A little after midnight on January 30, they assaulted the Nra Trang perimeter. All-day long, from Quang Tri to Ca Mau, in a barrage of rockets and mortars, they attacked provincial capitals and divisional headquarters. No target was too formidable. They attacked Bien Hoa, Cam Ranh Bay, and even Tan Son Nhut. Vietcong and NVA soldiers were fighting in the streets of Hue, DaNang, and Saigon itself.

In a sense, the Tet battles of 1968 saw both sides fall victim to their own propaganda. When NVA divisions began converging around the combat base at Khe Sanh in early January, President Johnson worried about a “second Dien Bien Phu.” MACV welcomed the prospect. According to his body-count scorekeeping, the enemy was on the ropes. Dien Bien Phu would be refought and he would win it. He threw the bulk of his combat manuverables into I Corps to engage NVA regulars. By the morning of January 31 “The Front” was outside his back window, F-100s were flying tactical air support over the streets of Saigon, and there were fire fights in progress on the U.S. Embassy lawn. The ARVN had gone on holiday routine.

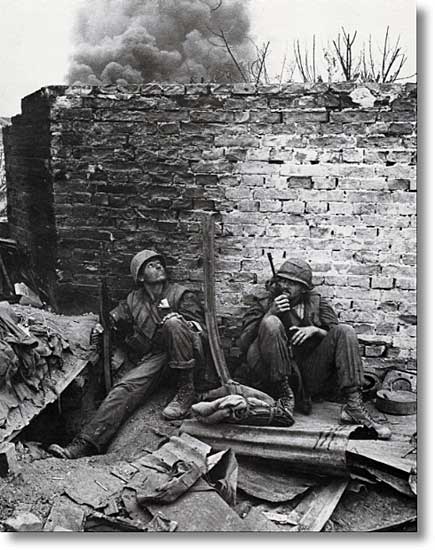

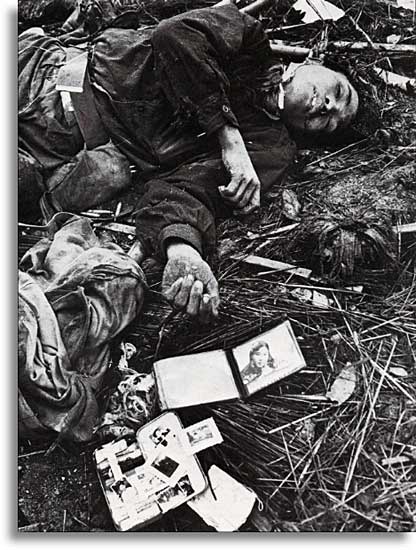

But all was not going according to plan for the attackers. They found no “general uprising” to welcome their “general offensive.” Confident of victory and conscious of history, Communist guerillas fought their way into every city in the country and foundered there, fish out of water. Whether they acted as a matter of policy or out of frustration at their compatriots’ lack of ardor, some of the worst atrocities charged to their account occurred during the twenty-six days they held power in sections of Hue. Afterward, more than 3,000 bodies were found in mass graves around the city. Some had been buried alive

After the fact MACV would take comfort from the enormous numbers of enemy dead. His spokesmen would call the Tet offensive a “last ditch struggle” and compare it to the German winter offensive of 1944. But something was wrong. It became apparent that the enemy had taken MACV by surprise. His spokesmen said contradictory things about the enemy’s intentions. His own intentions were unclear. He seemed not to be in control. He was fighting the enemy’s war in the enemy’s good time. If the enemy chose to fight on MACV’s front porch, the enemy had the capability. If the enemy chose western Quang Tri Province MACV would hasten to meet him there.

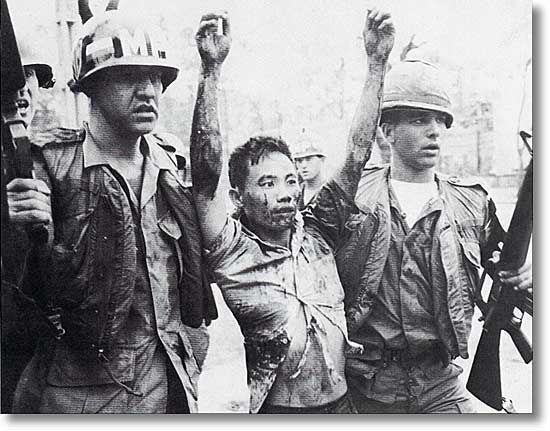

With Tet, Vietnam finally got America’s attention. Millions of Americans watched the battle for Saigon on the evening news, and many who were not personally involved took notice for the first time. In the winter dusk of American as 1968 proceeded, dreadful sights were broadcast. The cameras recorded burnings, executions, even the sight of American soldiers falling in battle. MACV was powerless to control news media that no longer trusted him. He had sincerely believed there would be nothing to hide.

Lyndon Johnson tried to explain it away and his own credibility suffered. On February 27, the avuncular Walter Cronkite, a public surrogate, pondered the question of whether “the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in stalemate.” The decade that had opened in the winter sunshine of Kennedy’s inaugural was flickering out in a confusion of shadows and unwholesome light.